Air Resistance in Cycling – the Invisible Brake

These articles might also interest you:

- Aero Sensors in Cycling – Notio, Aerosensor & Co. — 28.11.2025

- How We Calculate Aerodynamic Drag at RaceYourTrack — 11.11.2025

Air resistance in cycling – the invisible brake

👉 To the Watts ↔ Speed Calculator: Bike Calculator

We think about air resistance most when it really hurts: headwind, tired legs, and the next hill already in sight. That’s usually the moment when the questions start: Is my position on the bike right, does it help if I make myself smaller, and why does it all feel so unbelievably heavy?

Our instinct says: make yourself as small as possible. At the same time, we need enough air to breathe and want to keep a clear view of the road ahead. To understand these apparent contradictions, it’s worth taking a closer look at what air resistance in cycling actually is.

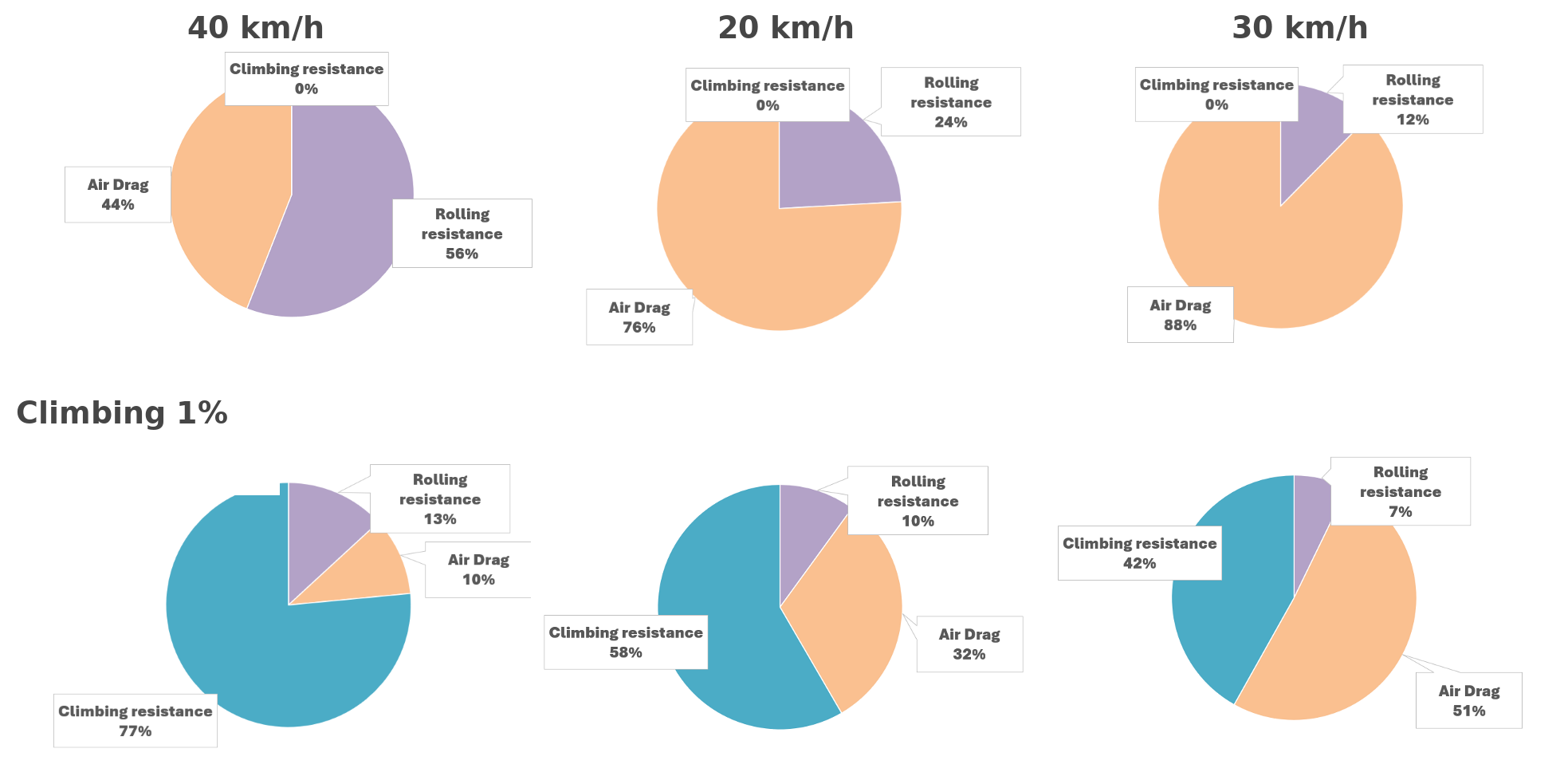

A look at the forces – what the graphic above shows

The header graphic shows how the shares of air resistance, rolling resistance, and gradient resistance contribute to total power.

From left to right, the speeds 10, 20, and 30 km/h are shown.

Top row: riding on flat terrain (0% gradient).

Bottom row: the same speeds at a 1% gradient.

Flat terrain (0% gradient):

- 10 km/h: about 44% of the power goes into air resistance, 56% into rolling resistance. Aerodynamics is already present but not yet dominant.

- 20 km/h: air resistance rises to around 76%, rolling resistance drops to 24%.

- 30 km/h: roughly 88% of the power is eaten up by air resistance, only 12% goes into rolling resistance.

Gentle climb (1% gradient):

- 10 km/h: about 77% of the power goes into climbing (potential energy), only 13% into rolling resistance and 10% into air resistance.

- 20 km/h: the climb still accounts for around 58%, air resistance is already at 32%, rolling resistance at 10%.

- 30 km/h: at high speed on this slight gradient, around 51% of the power goes into air resistance, 42% into climbing, and 7% into rolling resistance.

The key message: On flat terrain, air resistance dominates more and more as speed increases. On a climb, altitude gain initially plays the bigger role; as speed goes up, air resistance catches up until both effects are of similar magnitude.

Note: The percentages in the graphic were calculated using a simple physical model. The assumptions are a total mass of 80 kg for rider and bike, a rolling resistance coefficient (c_r) of 0.003, an air density of 1.2 kg/m³, a drag coefficient (c_w) of 0.4, a frontal area (A) of 1.0 m², and a drivetrain efficiency of 1.0 (i.e. lossless). These values are deliberately simplified and are meant to illustrate the relative proportions of the resistances rather than reproduce a specific real-world ride exactly.

Why everyone in cycling talks about watts

In modern cycling, everything revolves around watts. Power meters are widespread, and in tests or marketing you constantly read claims about how many watts a bike or helmet can save.

This sounds very concrete because many riders know their training zones in watts. What really matters, however: these numbers are only meaningful if the conditions under which they were determined are clear, especially

- at what speed

- at what rider weight

- in which position and on which bike

Without this context, any stated watt saving is very vague. Air resistance strongly depends on speed. A saving that looks impressive at very high speed can be much smaller at moderate pace.

In short: watt numbers from tests are mainly useful for comparing setups under very specific conditions – they are not a universal promise for every riding situation.

What air resistance really depends on

Air resistance on the bike is essentially determined by three factors:

- Shape of the overall system

In the wind, it’s never just one part that matters, but always the entire system:

- rider

- bike

- helmet

- clothing

- position

plus add-ons like lights, bottles, or bags. All of this together determines how cleanly the air flows around the system and how many vortices are created.

- Frontal area

Frontal area is, simply put, the area you present to the wind when viewed from the front. An upright posture with broad shoulders creates a larger frontal area; a lower, more compact position reduces it.

In practice, shape and frontal area are usually not known exactly. That’s why they are often combined in cycling into a single parameter, typically referred to as CdA.

- Speed and wind

For air resistance, the important quantity is not just the bike’s speed relative to the road, but the effective speed relative to the air. In other words:

- riding speed plus headwind

- riding speed minus tailwind

That’s why the same number on your head unit can feel completely different depending on wind direction.

Why air resistance feels so brutal

These three factors do not contribute equally to resistance. For how it feels on the bike, speed is the deciding factor.

- At low speed, air resistance plays a relatively minor role.

- As speed increases, the force from air resistance grows disproportionately. A small increase in speed suddenly requires a lot more power.

- Anyone who has tried to ride their absolute top speed on the flat knows the feeling of hitting an invisible wall: air resistance rises so sharply that extra watts barely translate into extra speed.

In simple terms: when speed goes up significantly, the power required to overcome air resistance rises much faster than the speed itself.

Air resistance is not an additive quantity

A common misconception is that you can simply add up the effects of individual components. In marketing claims, you often read that a bike saves a certain number of watts and a helmet saves some more.

But air resistance is not an additive quantity. There is no such thing as “the air resistance of the bike” plus “the air resistance of the helmet” that you can neatly sum up. What matters is always the entire system of rider and equipment.

The helmet influences how air flows over the head and back. The frame shape changes the flow around the legs and wheels. Flapping clothing can partially cancel out the aerodynamic benefits of the equipment. All components interact and jointly shape the airflow.

The consequence: watt savings from individual parts cannot simply be added. What counts is always the effect of the complete package in your actual riding position.

Air resistance, gradient, and potential energy – what slows you down when

Air resistance is not always the main enemy. Depending on the course profile, sometimes aerodynamics dominates, sometimes the gradient – exactly what the header graphic illustrates.

-

Flat roads and high speeds

Here, most of your power goes into fighting air resistance. If you want to get faster on such terrain, you should mainly work on aerodynamics, position, and clothing. -

Steep or longer climbs at lower speeds

On climbs, the gradient dominates. A large part of your work goes into building potential energy – gaining altitude. In this case, the total weight of rider and bike becomes much more important than a perfectly aero position. -

Gently rolling terrain

In many real-world scenarios, you’re somewhere in between. Moderate gradients meet medium to higher speeds. In this zone, both a reasonable system weight and solid aerodynamics pay off. Extreme solutions are rarely necessary, but a slightly lower, calmer position already brings noticeable benefits.

Conclusion

Air resistance is the key factor for speed on flat and fast sections. At its core, it depends on shape, frontal area, and effective speed relative to the air – and it increases disproportionately as speed rises.

Watt numbers from tests and marketing only make sense when interpreted in the context of speed, position, and test setup. Aerodynamics is always the result of the entire system of rider and equipment and cannot be broken down into simple, additive building blocks.

If you understand these basic relationships and deliberately tweak your position, clothing, and riding style, you can significantly reduce air resistance and ride noticeably faster on the same route with the same power.

Determining your CdA from real rides – with RaceYourTrack

If you don’t just want to feel your personal drag coefficient CdA, but actually calculate it from real rides, you can use the extended implementation of the Chung method. This is exactly where RaceYourTrack comes in: based on your power and GPS data, CdA is determined from your laps and fed directly into a physically consistent simulation of your course. That way, you can see how aero you really are, how position changes affect you, and what speed is possible with your current aerodynamics.

You can find all the details in our article How do we calculate air resistance at RaceYourTrack?.